Facing the City. Mylius in Mind.

Using an almost forgotten technique and immense patience, photographer Niklas Görke captures 21st-century Frankfurt—just as Carl Friedrich Mylius did more than 160 years ago. The result is a unique panorama that reveals a city in transition and is much more than a mere homage.

Niklas Görke, Mainpanorama (Detail), 2022, © Niklas Görke

Hier den Artikel auf Deutsch lesen.

Frankfurt finds itself along the banks of the Main. The river runs through the city like a prime meridian; and, like so many Frankfurt stories, this one also begins on its shore. There, in February 2020, stands my wooden 4x5-inch large format camera. Beside it is my cargo bike, loaded with a black box fitted with red windows. Curious passers-by ask what exactly I am doing.

Each Image a Unique Piece

Just as Carl Friedrich Mylius did around 160 years ago, I photograph using the historic collodion process of 1851. What Mylius once transported on a handcart—camera, chemicals, and darkroom—now fits on my cargo bike, for which I have built a custom-made mini photo lab. Without it, work on location would be impossible: for a wet collodion photograph, a glass plate is coated with a mixture of nitrocellulose (“collodion”) dissolved in ether and ethanol, along with iodide and bromide. The plate is then sensitized in a silver nitrate solution and must—still wet—be exposed and developed immediately. During development, the silver salts are reduced to metallic silver—exactly where and to the extent that light struck the plate. The chemicals can only react with each other while the plate remains wet. Afterwards, the plate is fixed, rinsed, and varnished to protect it from oxidation. The glass plate is a negative from which a positive print can be made. If, instead of glass, a black-coated aluminium plate is used, a direct positive is created—a true one-of-a-kind image.

Niklas Görke with his Equipment by the River Main, Photo: Freddy Langer

Is it really worth putting oneself through all this today? Wet collodion photographs are truly unique. No two images are alike. Every step in the process leaves its own traces—small blurs or chemical streaks, for instance. They create a field of tension with the actual subject. When a photograph is powerful, the subject asserts itself through these traces. Here, photography once again becomes an object—imbued with the special aura of the original.

Main Panorama 2.0

In February 2020, everything was ready for the first live test by the Main. It worked. Over the following six months, I cycled through Frankfurt, exposing around 400 plates. Despite COVID, the exhibition at the 1822 Forum took place; it went well. While searching for a new project, Carl Friedrich Mylius came back to mind: during my research, I came across a Städel Stories article about Mylius. In it, Dr Kristina Lemke also describes the Main Panorama, which Mylius created from 31 plates after photographing Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen from the opposite banks of the Main, moving the camera 100 metres at a time over a distance of 2.5 kilometres. How about a new edition—the same technique, but modern-day Frankfurt? Before long, I knew the Main Panorama inside out, both the version published in the book “Das Alte Frankfurt am Main” edited by Dr Meyer-Wegelin, and the one held by the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.

View of the exhibition “Frankfurt forever!” featuring the Main Panorama by Carl Friedrich Mylius, photo: Städel Museum / Norbert Miguletz

I set myself the following conditions: I work with wet collodion on glass plates, choosing formats of 5x7 inches (approximately 13x18 cm) and 4x5 inches (approximately 10x13 cm). The panorama must already function when the glass plates are placed side by side. (Mylius assembled his panorama from paper prints; unfortunately, his original glass plates have been lost.)

Old and New Challenges

In February 2022, my 75-year-old Magnola 5x7-inch plate camera once again stands by the Main—this time opposite the ECB. But the very first series of images reveals a host of problems: it starts with the junctions between the individual exposures. Where one plate ends, the next must align in a way that appears as a logical and natural continuation of, for example, a building. To be more flexible with spacing and alignment, I decide to also use smaller plates in the 4x5-inch format. I divide the overall route into sections between the bridges. Before photographing a new section, I determine the precise camera positions.

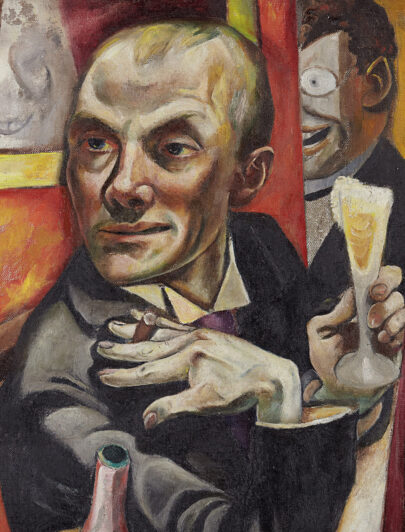

Niklas Görke, Mainpanorama (Detail), 2022, © Niklas Görke

Another problem arises: if I place the junctions along the quay wall to create a continuous riverbank, parts of the buildings behind it are duplicated on the adjacent plates. If I instead place the junctions at the first row of buildings behind the riverbank, around 20–50 metres of the riverbank are lost. Mylius faced the same issue. Now I understand why, in his panorama, the junctions sometimes align at the buildings but not at the river’s edge—as seen in the cut-off ships. The explanation: a camera captures a scene within a cone originating from the focal point of the lens. In two-dimensional terms, this cone becomes an infinitely long V, with an angle of view dependent on the lens. Where the two “Vs” from different camera positions cross, they match; everything behind overlaps, and everything in front is omitted. Like Mylius, I decide to place the junctions at the first row of buildings behind the riverbank, accepting the loss of a few metres of riverbank and the partial cropping of bridges.

Niklas Görke, Mainpanorama (Detail), 2022, © Niklas Görke

Mylius did not change his location for every single exposure. The two outermost pairs of images are pans taken from a single position, and possibly at least two other points as well. In those places, moving would not have offered any advantage. Moreover, Mylius slightly panned most of his shifted exposures to the east or west. This made it easier to adjust the junctions and avoid the duplication of taller buildings in the background. Mylius had it easier in this regard: there were no skyscrapers that, due to the winding riverbank and overlapping fields of view, appear multiple times—as they do in my panorama. I see it as similar to a walk along the Main riverbank—there, too, one sees the towers from constantly changing perspectives.

Mylius was surely concerned with more than just avoiding perspective distortions. He made aesthetic as well as pragmatic decisions in order to complete his panorama. Mylius was a pioneer, and my respect for his work grows with every day I spend by the Main. And sometimes, I stand at a single spot for what feels like an eternity, waiting for everything to come together. Sometimes the chemistry doesn’t work; other times, I miss the perfect light because someone distracts me.

Farewell Gift

In June, my wife received an offer for a position in Boston, USA. Departure was set for mid-August. We decided to take it. I was only halfway through the panorama, and despite everything we now had to organize, I was determined to finish. On the night before our flight, I varnished the last of the 32 plates of the now complete panorama (446 cm × 22 cm) and carefully packed them into a box in my studio at the time. The box is still there.

They say “I’ve left a suitcase in Berlin.”

I have left a Main Panorama in Frankfurt.

A love letter and a farewell gift to my city.

By the Main.

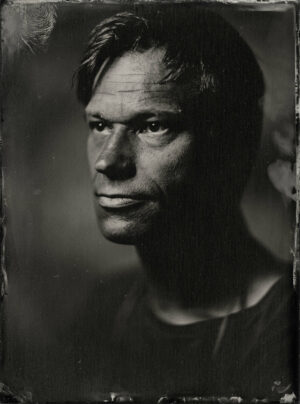

Niklas Görke, Portrait, Photo: Thilo Nass

Newsletter

Wer ihn hat,

hat mehr vom Städel.

Aktuelle Ausstellungen, digitale Angebote und Veranstaltungen kompakt. Mit dem Städel E-Mail-Newsletter kommen die neuesten Informationen regelmäßig direkt zu Ihnen.