A Portrait and its Loss

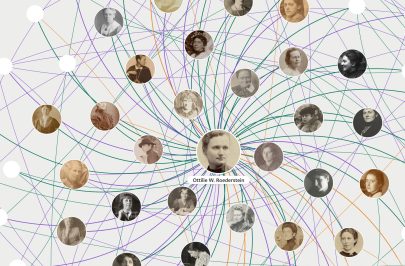

Ottilie W. Roederstein's portrait of the Frankfurt dermatologist Karl Herxheimer was donated to the collection in 1952. Who was the donor? And how did the painting come into her possession?

Hier den Artikel auf Deutsch lesen.

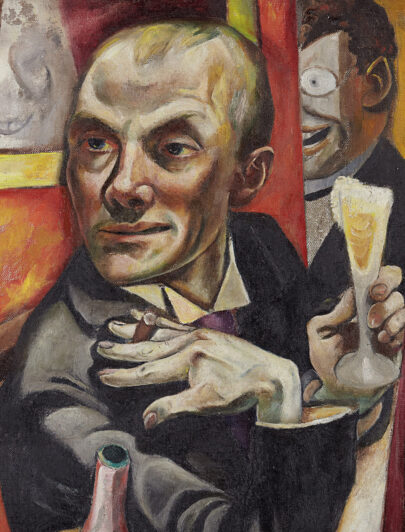

Karl Herxheimer (1861–1942) was one of the leading physicians of his time. He was the first director of the Frankfurt Clinic for Skin and Venereal Diseases, which he headed from 1894 to 1930, and co-founder of Frankfurt University. The portrait of Prof. Herxheimer by Ottilie W. Roederstein shows him around 1911, the year in which the highly respected professor celebrated his 50th birthday.

Roederstein's portrait immortalizes him in three-quarter profile against a warm grey-green background. It shows him confidently dressed in a dignified black suit with a white stand-up collar. He wears a prominent broad mustache. His alert blue eyes seem to fix the viewer. Whether this painting was commissioned by a person or institution on the occasion of his round birthday or whether Herxheimer himself asked the artist, whom he knew personally, is unfortunately not known.

„before his departure for Theresienstadt“

But how did his portrait come into the collection of the Städel Museum? A handwritten letter from a certain "Mina Rode" in the Städel Archive reveals the painting's tragic origins: "In my possession [I have] a painting by Geheimrat Prof. Dr. Karl Herxheimer, which he [gave] to me before he left for Theresienstadt at the end of August 1942," she wrote on October 17, 1952 to the then director of the museum Ernst Holzinger. "I would like to give the picture, painted by O.W. Roederstein, to the Städelsche Kunstinstitut, as I would like to see it in good hands."

Persecuted and stripped of his rights

When the National Socialists came to power, Herxheimer – emeritus professor since 1929 – was persecuted as a Jew. The professor's teaching license was revoked in 1933. From 1938 he was no longer allowed to practice. But he did not want to leave Frankfurt, although he owned a house in Switzerland. Friends were finally able to convince him and his housekeeper Henriette Rosenthal, who lived with him, that they should secretly flee to Switzerland in the summer of 1942. At that time, however, all Jews living in Germany were already forbidden to leave the country and had to wear the so-called "yellow star". Both were forced to move to a so-called "ghetto house" in Friedrichstraße in October 1941. They no longer had control over their assets, which were seized by the government. Their courageous helpers provided them with forged passports and worked out an escape plan.

Tragically, however, the high-risk plan failed due to a mishap. Because of an alleged violation of an anti-Jewish regulation, Henriette Rosenthal – a neighbor had denounced her – was imprisoned by the Gestapo. When the news of the ordered "departure" to Theresienstadt reached her, she was in prison. On September 1, 1942, Karl Herxheimer, who was over eighty years old, was deported to Theresienstadt together with Henriette Rosenthal. There he died of a heart ailment on December 6, 1942. Henriette Rosenthal passed away only a few weeks after him.

Mina Rode

Mina Rode (1873–1959), to whom Herxheimer had left his portrait before he was deported, was a well-known Frankfurt violinist. She played a Guarneri violin, had attended Hoch's Conservatory, performed internationally, and later also gave music lessons. There are only few biographical sources about her, however. A photograph in the Roederstein-Jughenn Archive of the Städel shows Rode in the company of a Frankfurt couple who were friends of Ottilie Roederstein. Was she possibly acquainted with the artist?

Unknown photographer, Mina Rode (1st from left), Sig. St. A. OR 21, Roederstein-Jughenn Archiv

On Thursday we have to leave Frankfurt

Only few personal documents by Herxheimer and Rosenthal which survived provide a glimpse of the unfathomable circumstances in which they found themselves the last days before their deportation. On August 28, 1942, Henriette Rosenthal wrote to the nurse who had cared for both of them: "To our great pain, this is a farewell letter. On Thursday we have to leave Frankfurt and move to Theresienstadt in Bohemia."

But the personal testimonies and recollections of people close to them also provide an unbearable insight into this difficult time. Among these people was Gertrud Roesler-Ehrhardt, née Blum (1896-1992), the daughter of the medical doctor Ferdinand Blum, who was a friend of Karl Herxheimer. Blum – who managed to emigrate to Switzerland in 1939 – and his daughter had been involved in the escape plan. Roesler-Erhardt – who according to the "Nuremberg Race Laws" was considered a so-called "half-Jew" – lived not far from Herxheimer at Arndtstraße 51 and from there, together with her sister Pauline Jack, née Blum, and the British sisters Ida and Louise Cook, helped persecuted persons to emigrate to England. Blum's daughter Jack was a trained opera singer and music teacher. It is therefore conceivable that Rode was one of her contacts.

A portrait of Prof. Dr. Herxheimer

It was also Roesler-Erhardt who was called as a witness after 1945 in the course of the restitution claims against the German Reich pursued by the total of 27 heirs of Karl Herxheimer (since Herxheimer had no children and his wife had already died in 1928, the descendants of his eleven siblings were his heirs). In a hearing before the State Office for Property Control and Restitution in Hesse, she stated the following: "I took into my possession a portrait of Prof. Dr. Herxheimer by the painter Ottilie Rödersheim [sic] on the penultimate day before his deportation." Could this Roederstein portrait of Herxheimer actually be the painting that Mina Rode donated to the Städel in 1952?

In comparison with Rode's written statement that Herxheimer "gave" her the portrait "before he left for Theresienstadt," this statement probably only makes sense if Herxheimer gave it to Roesler-Erhardt to pass it on to her. That Rode could have come into possession of the portrait in this way seems quite possible, since at that time non-Jewish persons who showed "friendly relations with Jews" were threatened by law with temporary protective custody.

Karl Herxheimer, Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt am Main, S7P 06321

In memoriam

It is no longer possible to reconstruct whether Herxheimer gave his portrait to Rode in return for help received or out of sheer desperation in the face of his impending deportation. Despite intensive research, gaps in the record remain. Rode donated the painting – while explicitly mentioning its provenance – to the Städel in 1952 because she wanted it to be "in good hands”. Since it is proven that Herxheimer had to part with the painting due to persecution, the Städel Museum registered it in the database lostart.de.

The portrait by Roederstein shows the Frankfurt dermatologist at the height of his success and pays tribute to his persona. At the same time, the painting, which he lost in August 1942, is inscribed with the tragic fate of persecution of the sitter and former owner. This article shall honor his life and fate.

Newsletter

Wer ihn hat,

hat mehr vom Städel.

Aktuelle Ausstellungen, digitale Angebote und Veranstaltungen kompakt. Mit dem Städel E-Mail-Newsletter kommen die neuesten Informationen regelmäßig direkt zu Ihnen.