An intriguing fragment

A unique glimpse into 17th-century medical practice, social life, and the staging of public dissections—captured in a masterpiece that remains powerful, even in its fragmented state. Curator Norbert Middelkoop of the Amsterdam Museum on Rembrandt’s “Anatomy Lesson of Dr Jan Deijman”.

Early in 1656, a group of surgeons approached Rembrandt to have their portraits painted during an anatomy lesson. Among members of the Amsterdam Surgeons’ Guild, this subject was considered highly suitable to visualize both their erudition and mutual bond. In the guild chamber, four previous painted “Anatomy Lessons” were already being cherished. The fitting occasion for the commission was the first public anatomy lesson to be given by Dr Jan Deijman, who had been appointed ‘praelector anatomiae’ by the city government three years before. As usual, the corpse of an executed criminal was used as the ‘subiectum anatomicum’. On 27 January 1656, Joris Fonteijn, a Flemish tailor with a substantial criminal record, was sentenced to the noose. After the execution, his body was made available to the surgeons.

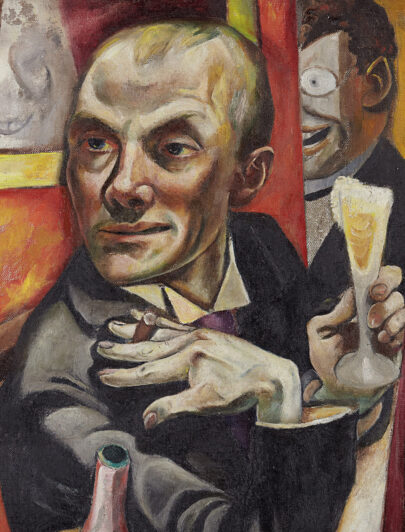

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), Anatomy Lesson by Dr Jan Deijman (fragment), 1656, Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam

Public Anatomy Lessons: More than Education

Public anatomy lessons were organized by the guild on a regular basis and conducted by an academically trained doctor, the ‘praelector anatomiae’. He not only performed anatomical dissections on dead bodies but also provided other forms of medical education for the surgeons and their pupils, like osteology.

Usually public dissections would take more than a day and were held in winter, as the corpse remained in good condition longer when temperatures were low. Although originally established for educational purposes, by the end of the 16th century these annual anatomy lessons had grown into social events and attracted many spectators. We have to realize that surgeons, who feature so prominently in anatomy paintings, were not doctors as we understand the term today, but craftsmen. They were authorized to treat external complaints and carry out only minor ‘operations’, the most common of which were bloodlettings and haircuts.

Egbert van Heemskerck, The Surgeon Jacob Fransz and His Family, 1669, Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam

Furthermore, none of the painted anatomy lessons should be considered an exact representation of the event itself. In anatomical terms, they are far removed from reality. Like in other corporate group portraits, the sitters had to pay for their own portraits; this is why only a limited number of surgeons is depicted. Most of the “Anatomy Lessons” were painted not long after the appointment of a new ‘praelector’, like in Deijman’s case. These group portraits thus commemorated the tenure of a ‘praelector anatomiae’ and, for the surgeons depicted, their membership of the Surgeons’ Guild.

Rembrandt’s Composition

In selecting a theme for this painting, Deijman had to surpass his predecessor Nicolaes Tulp, who had himself portrayed as the protagonist of an anatomy lesson in 1632, while Rembrandt had to find original solutions—yet again—to the challenge of portraying a group of people around a dissecting table. The choice of a brain dissection would not only allow the ‘praelector’ to show off his anatomical skills, but would also draw attention to the most elevated part of the body.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, Mauritshuis, The Hague

(Not on view in the exhibition “Rembrandt’s Amsterdam. Golden Times?”)

Even from the surviving part of the canvas, it becomes clear that the element of time is very much present. Leading our eyes from the feet of the subiectum to the empty thorax, Rembrandt shows us that the body has been opened and the various perishable organs have been removed. The praelector’s assistant standing next to the table has just removed the black cloth covering the corpse and is holding the skull-cap in his hand, while Deijman is showing his audience the shape of the ‘falx cerebri’, located between the two parts of the human brain. His gesture refers to the age-old ‘memento mori’ message, given the similarities in both form and name between this ‘falx’ and the reaper’s sickle, the symbol of Death himself.

What Remains of Deijman’s Anatomy Lesson

Rembrandt’s “Anatomy Lesson of Dr Jan Deijman” was damaged in a fire in 1723. What remains of the large canvas is the central part showing the anatomical ‘action’: the exposure of the human brain. Whereas poor Dr Deijman has lost his head in the disaster, the corpse lying on the table was among the few ‘survivors’. Thanks to this, we can still enjoy one of the most successful examples of foreshortening in art history.

Rembrandt’s small preliminary drawing of the original composition shows seven more surgeons sitting on a semi-circular tribune and watching Deijman’s performance. Their movements and gazes must have contributed to the huge impact of the “Anatomy lesson of Dr Deijman”. Originally, beholders of the painting were given the feeling to be embraced by the wooden walls of the anatomy theatre; as if they were the privileged witnesses to the important event as well. But even in its current state as a fragment, the painting continues to make a deep impression.

Newsletter

Wer ihn hat,

hat mehr vom Städel.

Aktuelle Ausstellungen, digitale Angebote und Veranstaltungen kompakt. Mit dem Städel E-Mail-Newsletter kommen die neuesten Informationen regelmäßig direkt zu Ihnen.