Guardsmen, Governors and Guild Members

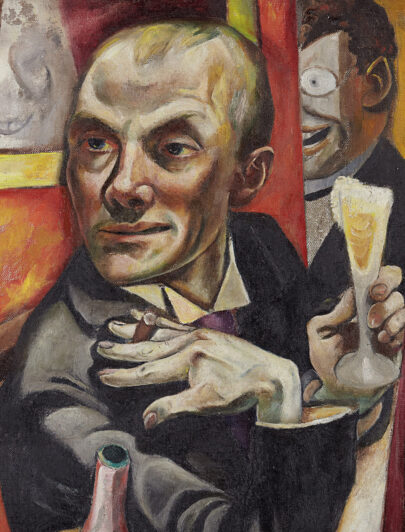

Amsterdam in the 17th century: a city in transition. Curator Norbert Middelkoop of the Amsterdam Museum explains how the group portraits of the time document the responsibilities and social networks of civic guards, governors, and guild members. These paintings provide insight into the city’s social system and reveal the connections between art, social status, and public life.

Amsterdam’s great appetite for group portraits in the 17th century was largely due to the city’s economic growth. The booming economy and the large numbers of immigrants attracted by it had created the basis for a well-organized urban society in which prosperous citizens had the opportunity to take on responsible tasks within a large network of semi-public positions. The many corporate group portraits celebrate their responsibilities.

Although the collective tasks were temporary, the portrait was a lasting reminder of their tenure. Moreover, it provided appropriate interior decoration for the building in which the organisation resided. The paintings’ presence instilled respect among visitors or residents, particularly when group portraits depicting prior squads, companies or boards of governors were in the immediate vicinity. And later generations in comparable positions derived a part of the desired status from them.

Commemorating Responsibility

The initiators of a commission acted jointly, although in principle each of them paid for their individual likeness. The painter was paid indirectly for the portraits of employees, residents of the institutions and other additional figures; the fee was included in the price paid by each participating protagonist. Through their presence, they provide a modest narrative element underlining the message of charity and sound governance. The painter also had a compositional reason for including additional figures. Servants entering the room provided him with a logical pretext to have the faces of the sitters pointing in the same direction, towards the light.

Commissioning a group portrait depended on the availability of sufficient wall space in the buildings: no wall, no commission. In 1653, no less than eighty-five paintings were present in the three Amsterdam civic guard houses, the earliest dating from 1529. Most of these showed squads and companies of male citizens, portrayed while displaying their responsibilities in safeguarding their respective precincts. During the preceding decades, all three civic guard houses had been expanded, which had led to new commissions.

This trend had now come to an end, since the number of precincts was increased to 54, making it practically impossible to have group portraits painted for each of the companies. To crown the three series, the headmen of the civic guard houses decided to have their own group portraits painted.

Governors at the Table

Following the example of the civic guard, the charitable and correctional institutions also required appropriate decoration for their new new governors’ rooms, some of which were housed in confiscated former Catholic building complexes. In the 1610s, Cornelis van der Voort introduced a new type of group portrait, showing boards of governors at a meeting table. He developed a placement hierarchy for the people depicted. This was determined by the order in which the governors joined the board. The longest-serving members sit in the best light in the foreground, while those who joined later sit further back, and the most recently appointed members are depicted standing.

An important driver for a commission was the periodic renewal of the group of officials as a whole. In the Surgeons’ Guild, one of the factors prompting an initiative for a group portrait was the appointment of a new praelector, after which the commission tended to follow in short order.

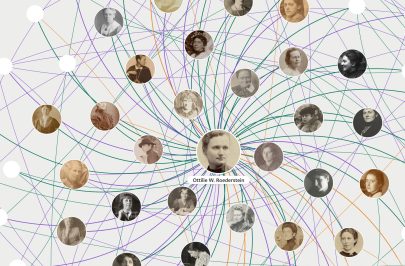

Women in Leadership

All the senior – unpaid – positions as officers in the civic guard as well as the governorships of the civic institutions and guilds were bestowed by the city’s burgomasters. Performing these tasks was not only considered part of a Christian’s duty, but it trained individuals in public administration, and also provided status, which – for the men – could result in a post in the Town Hall. Women had a special position. In the absence of alternatives in public life, a governorship of charitable and correctional institutions was the only position available to them, which is why the burgomasters primarily appointed widows, wives or daughters of male members of the urban elite. As a result, in most cases the female governors belonged to the same elite upper class as the leaders of the city government. Their origin in a class above that of their male colleagues gave them a strong position in the organizations.

Competition and Creativity

Competition between the civic organizations in their pursuit of ‘adornment and remembrance’ had a catalytic effect on issuing commissions and on the availability of outstanding portraitists, who were attracted by Amsterdam’s thirst for portraits and, in competition with their fellow painters, could develop their artistic skills and continue to innovate the genre. That extraordinary balance between supply and demand resulted in an unparalleled group of works.

Exhibition view, photo: Städel Museum – Norbert Miguletz

Newsletter

Wer ihn hat,

hat mehr vom Städel.

Aktuelle Ausstellungen, digitale Angebote und Veranstaltungen kompakt. Mit dem Städel E-Mail-Newsletter kommen die neuesten Informationen regelmäßig direkt zu Ihnen.